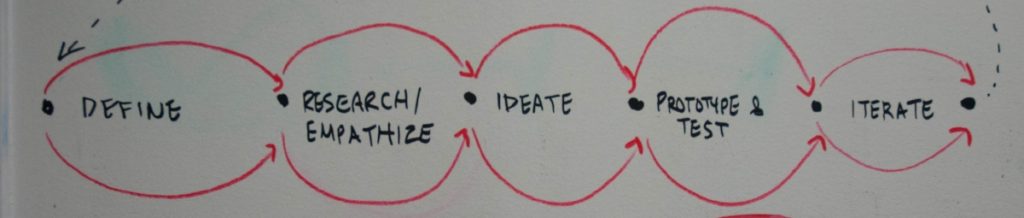

In September, I embarked on my first design sprint. In my role as designer, I will be working with others on the Capacity by Design project team to deliver design sprints for social good organizations but I wanted my first experience to be from the participant’s perspective. And so, I became a temporary member of the Carizon team during their sprint week. Carizon is an organization that focuses on strengthening mental health and wellbeing for families in Waterloo Region. I joined the intrepid group of Carizon employees who represented a number of programs across the organization and we embarked on five days of working together on a challenge they wanted to tackle within their organization. Together, we moved through the five phases of a design sprint which include defining and understanding the problem, doing research with people to gain a perspective on the problem, ideating around possible solutions, prototyping those solutions and finally conducting a round of testing with our audiences or users.

Here are some insights I gained from this design-sprint experience.

Trust the process

One of the things we heard on the first day of the sprint was that we needed to trust the sprint process and it’s underpinning of human-centered design. Hearing this, however, and living it during the week were two different things. I found this to be most challenging on Day 1 when we explored what we thought we would need to find out in order to understand more about our problem. We, in fact, developed quite a substantial list of things we thought we’d need to know in order to inform our eventual design of possible solutions.

With so much information to gather, we set out in groups of two or three on the following day to do our research with clients, staff and community to get their thoughts on what they felt they needed to support their family’s mental health and well-being. When we gathered together afterwards, it became clear that some pieces we had identified as vital to know at the outset had become less important. It helped me understand that that not only did we not have to have all the answers, we didn’t need to have all the questions either. Getting to experience this aspect of human-centred design was a valuable learning for me.

The challenge of thinking differently

In a design sprint, different ways of thinking are required. Divergent thinking is one way and it is used at various stages particularly during the ideation phase of a sprint. This is a time for creativity and imagining possibility. The goal is to generate a maximum number of ideas from a variety of people and perspectives in order to find a range of possible solutions. This part of the process felt hopeful and energizing for me.

Another mode of thinking that is required during a design sprint is convergent thinking. Convergent thinking involves an analysis or refinement of ideas – clustering like ideas and merging ideas that fit together in order to making decisions on how to move forward. After the freedom and creativity of the divergent phase, it felt almost painful to have to choose amongst ideas and concept, all of which felt like they were full of promise. I noticed that others in my group found this difficult as well.

Dynamic nature of design thinking

As much energy as the sprint process required, a surprising amount of energy was generated from investing in the process. Problems that are best addressed by design thinking are not trivial, but the tools we used at each stage made a ‘wicked problem’ more tangible and approachable. We worked hard and thought deeply and as we moved through each phase we gained momentum. Concepts and ideas began to build on each other, and this new-found energy propelled us forward.

Using constraints as a force for good

In the world of design, constraints are viewed as constructive and helpful to the development of solutions. This idea of embracing constraints at first sounded to me like it ran counter to the idea of design-thinking: wasn’t the point to develop a new approach to problems that are already pre-loaded with their own constraints such as lack of money, resources or time? Not so, I learned. Placing constraints around a problem helps, in fact, to bring the problem into focus. It aids in the development of potential solutions that are grounded in the reality of the organization. Design sprints themselves make conscious use of the constraint of time, for instance, to move the process forward.

Important learning is not lost

There was some worry amongst the Carizon team that some of the great ideas that were generated would be lost as we made decisions on what to prototype. What I observed, however, was that the essence of what was powerful for each sprinter infused itself into each prototype. In the creative act of making something, ideas are combined, shared and cycled through. Everything you learn as the process unfolds, comes with you in some way and informs how you think – not just the ideas you generated or those devised within your smaller group, but what has been learned through mutual discovery and ideation.

I am grateful to have shared this first sprint experience with Carizon. We’re getting ready for our second sprint, and like any experience that energizes and inspires, I can’t wait to have the sprint experience all over again!